One of the great pleasures of metaphysical poetry is unlocking it, figuring out how the metaphors fit. It’s a pleasure akin to the pleasure of making up categories. Rooting around the web today, trying to learn something about this poem, I came across a delightful old (1965) PMLA article that takes the poem’s central irony very, very seriously—to a fascinating result. So, the first thing to say about this poem regards the title: this is a love poem that borrows its title from a serious, official theological procedure. Canonization, the process of declaring a person a saint, follows strict bureaucratic rules. John Clair’s 1965 essay argues quite simply and persuasively that, in Donne’s poem ironically borrows the five-step canonization process for its structure. Thus, each stanza corresponds to a stage in the process of declaring someone a saint. The process, as Clair outlines it was as follows: 1) Investigation into the subject’s reputation, 2) Inquiry into the subject’s practice of the heroic virtues (i.e. faith, hope and charity as well as prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude), 3) Investigation of alleged miracles, 4) Scrutiny of the subject’s writings, and 5) Examination of the burial place an identification of the remains or relics.

Thus, [Donne's] lovely third stanza makes the fusion of two into one in love the miracle itself.

It’s a lovely, nerdy little observation, dutifully attentive to doctrinal theology and thus very out of fashion with contemporary criticism. I adore it. It deepens the poem for me. I have an even greater respect for the ingenuity of Donne’s conceit, which is intellectually satisfying as all such categorizations are. (Each stage in the process gets exactly a stanza; a five-step process maps perfectly onto a five-stanza poem.) But this intellectual pleasure, like a solved puzzle, is only part of it, for linking the stanza to the investigation of miracles enlivens and enriches the metaphors within it: the paradoxical combination of eagle and dove, the phoenix rising from the ashes, the more than miraculous stability of a love that persists.

28 February 2006

Piecing metaphors

Anne Fernald on John Donne's "The Canonization":

Reality

Karen Armstrong on how 'Positive thinking' can be a route to spiritual and political disaster:

Increasingly it is becoming unacceptable to voice legitimate distress. If you lose your job, become chronically ill, or fall prey to loneliness or depression, you are likely to be told - often abrasively - to look on the bright side. With unseemly haste, people rush to put an optimistic gloss on a disaster or to suggest a patently unworkable solution. We seem to be cultivating an intolerance of pain - even our own. An acquaintance once told me that quite the most difficult aspect of her cancer was her friends' strident insistence that she develop a positive attitude, and her guilt at being unable to do so. [...](via wood s lot)

As TS Eliot said, humankind cannot bear very much reality. Some forms of religion encourage us to bury our heads in the sand to block out the suffering that surrounds us on all sides. The rich man in his palace can reconcile himself to the plight of the poor man at his gate by reminding himself that this is part of God's bright and beautiful plan; those who suffer poverty and oppression in this life will be recompensed in the hereafter. [...]

This is lazy, inadequate religion. If we deny the reality of suffering, we will ignore the distress of others. At its best, religion requires the faithful to see things as they really are.

27 February 2006

As old as speech

John Steinbeck, born on this day in 1902

John Steinbeck, born on this day in 1902Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches - nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair.~ John Steinbeck, from his Nobel Prize banquet speech, 1962

Literature is as old as speech. It grew out of human need for it, and it has not changed except to become more needed.

The skalds, the bards, the writers are not separate and exclusive. From the beginning, their functions, their duties, their responsibilities have been decreed by our species.

Humanity has been passing through a gray and desolate time of confusion. My great predecessor, William Faulkner, speaking here, referred to it as a tragedy of universal fear so long sustained that there were no longer problems of the spirit, so that only the human heart in conflict with itself seemed worth writing about.

Faulkner, more than most men, was aware of human strength as well as of human weakness. He knew that the understanding and the resolution of fear are a large part of the writer's reason for being.

The wind's will

from "My Lost Youth"

I remember the gleams and glooms that dart

Across the school-boy's brain;

The song and the silence in the heart,

That in part are prophecies, and in part

Are longings wild and vain.

And the voice of that fitful song

Sings on, and is never still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

There are things of which I may not speak;

There are dreams that cannot die;

There are thoughts that make the strong heart weak,

And bring a pallor into the cheek,

And a mist before the eye.

And the words of that fatal song

Come over me like a chill:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

Strange to me now are the forms I meet

When I visit the dear old town;

But the native air is pure and sweet,

And the trees that o'ershadow each well-known street,

As they balance up and down,

Are singing the beautiful song,

Are sighing and whispering still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

And Deering's Woods are fresh and fair,

And with joy that is almost pain

My heart goes back to wander there,

And among the dreams of the days that were,

I find my lost youth again.

And the strange and beautiful song,

The groves are repeating it still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

~ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, born on this day in 1807

I loved him as a child, and so roaming his house was a memorable experience--countless stories in every room and behind every stick of furniture. (You can even take a virtual tour and catch a glimpse.) I bought a copy of Dante's Inferno on the way out: Longfellow wrote the first American translation in the years following his wife's tragic death.

I remember the gleams and glooms that dart

Across the school-boy's brain;

The song and the silence in the heart,

That in part are prophecies, and in part

Are longings wild and vain.

And the voice of that fitful song

Sings on, and is never still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

There are things of which I may not speak;

There are dreams that cannot die;

There are thoughts that make the strong heart weak,

And bring a pallor into the cheek,

And a mist before the eye.

And the words of that fatal song

Come over me like a chill:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

Strange to me now are the forms I meet

When I visit the dear old town;

But the native air is pure and sweet,

And the trees that o'ershadow each well-known street,

As they balance up and down,

Are singing the beautiful song,

Are sighing and whispering still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

And Deering's Woods are fresh and fair,

And with joy that is almost pain

My heart goes back to wander there,

And among the dreams of the days that were,

I find my lost youth again.

And the strange and beautiful song,

The groves are repeating it still:

"A boy's will is the wind's will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

~ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, born on this day in 1807

I loved him as a child, and so roaming his house was a memorable experience--countless stories in every room and behind every stick of furniture. (You can even take a virtual tour and catch a glimpse.) I bought a copy of Dante's Inferno on the way out: Longfellow wrote the first American translation in the years following his wife's tragic death.

26 February 2006

Space, time, and silence

Melbourne critic Chris Boyd talks with Athol Fugard:

(via you cried for night)

Fugard modestly describes himself as a storyteller and, elegantly, describes theatre as one of the “unplugged” arts. Film, he writes, leaves him cold. “Theatre -- and I am a practitioner of the purest form of it, ‘poor theatre’ -- is unique among the live arts in what it occupies: the three dimensions of space and then time and then silence.”Also, more in-depth conversation with Fugard on ‘Tsotsi’, truth and reconciliation, Camus, Pascal and “courageous pessimism”.

Asked if he is ever frustrated that theatre reaches only a niche audience -- rarely the young and rarely the masses -- he responds: “I simply can’t equate significance with a body count. Theatre goes to work on the matrix of a society in a way that film, TV etc with their audience of millions, can never do. I know this for a fact because I saw it happen in South Africa. Could there conceivably be a greater piece of contemporary theatre than Nelson Mandela sitting down at a table with the men who took way from him the best 27 years of his life, and drawing up a blue print for a New South Africa? You do know don’t you that while he was in prison, Mandela play Creon in a production by prisoners of Sophocles Antigone?”

“There you have it,” he concludes. Leaving his computer and the satellite coverage of the cricket match between India and Pakistan, “I go back to my desk and the play I am writing.”

(via you cried for night)

Vincent on Victor

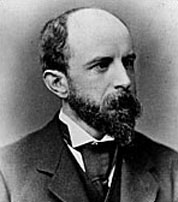

Victor Hugo, born on this day in 1802

Victor Hugo, born on this day in 1802From Van Gogh's letters to his brother Theo:

The Hague, 20-24, February, 1883

Last week I again read Notre Dame by Victor Hugo, which I had already read, more than ten years ago...Probably most people who read Notre Dame have the impression that Quasimodo was a kind of fool. But, like myself, you would not find Quasimodo ridiculous, and, like myself, you would feel the truth of what Hugo says, "For those who know that Quasimodo once existed, 'Notre Dame' is now empty. For not only did he live there, but he was the soul of it."The Hague, 30 March & 1 April 1883

I am reading Les Misérables by Victor Hugo. A book which I remember of old, but I had a great longing to read it again. It is very beautiful, that figure of Monseigneur Myriel or Bienvenu I think sublime.The Hague, April 11 1883

You spoke in your last letter of "exerting influence" in connection with your patient. That Mgr, Myriel reminds me of Corot or Millet, though he was a priest and the other two, painters. ...You surely know Les Miserables, and certainly the illustrations which Brion made for it too, very good and very appropriate.

It is good to read such a book again, I think, just to keep some feelings allive. Especially love for humanity, and the faith in, and consciousness of, something higher, in short, quelque chose là-huat.

I was absorbed in it for a few hours this afternoon, and then came into the studio about the time the sun was setting. From the window I looked down on a wide dark foreground -- dug-up gardens and fileds of warm black earth of a very deep tone. Diagonally across it runs a little path of yellowish sand, bordered with greeen grass and slender, spare young poplars. The background was formed by a grey silhouette for the city, with the round roof of the railway station, and spires, and chimneys. And moreover, backs of houses everywhere; but at that time of evening, everything is blended by the tone. So viewed in a large way, the whole thing is simply a foreground of black dug-up earth, a path across it, behind it a grey silhouett of the city, with spires, and over it all, almost at the horizon, the red sun. It was exactly like a page from Hugo, and I am sure that you would have been struck by it, and that you would describe it better than I.

Don't you like this little poem -- it is from Les Miserables:

If Caesar had given me

glory and war,

and if I had to leave

the love of my mother,

I should say to Great Caesar:

take back your scepter and your triumphal car

I love my mother more.

In the context in which it appeared in the book (it is a student's song of the time of the Revolution of '30), the "love for my mother" stands for the love for the republic, or rather love for humanity, in other words, simply universal brotherhood.

It is my opinion that no matter how good and noble a woman may be by nature, if she has no means and is not protected by her own family, in the present society she is in great, immediate danger of being drowned in the pool of prostitution

...I am reading the last part of Les Miserable; the figure of Fantine, a prostitue, made a deep impression on me -- oh, I know just as well as everybody else that one will not find an exact Fantine in reality, but this character of Hugo's is true -- as, indeed, are all his characters, being the essence of what one sees in reality. It is the type -- of which one only meets individuals.

23 February 2006

Fox Confessor Brings the Flood

This is old news to most, but I just found out about the forthcoming Neko Case album!! Listened to all the clips at Amazon--it sounds utterly phenomenal. As ANTI- proclaims,

This is old news to most, but I just found out about the forthcoming Neko Case album!! Listened to all the clips at Amazon--it sounds utterly phenomenal. As ANTI- proclaims,Neko Case’s fourth studio album, Fox Confessor Brings the Flood, is simply one of the most anticipated releases of 2006. Neko stands poised to break into the company of mavericks like Wilco, Beck, and Elliott Smith; like them she transcends genres and demographics, older fans swooning to her roots-infused vocal stylings as alternative kids dig her New Pornographers pop moves and David Lynchinspired, cinematic lyrics.(Includes downloads for "Star Witness" and "Hold On, Hold On." Pure bliss...)

22 February 2006

Fundamental mystery

All my life I've been harassed by questions: Why is something this way and not another? How do you account for that? This rage to understand, to fill in the blanks, only makes life more banal. If we could only find the courage to leave our destiny to chance, to accept the fundamental mystery of our lives, then we might be closer to the sort of happiness that comes with innocence.~ Luis Buñuel, born on this day in 1900

A 1945 portrait of Buñuel by Leo Matiz, photographer from Aracataca, Colombia.

(View work by other Colombian photographers.)

Departure

It's little I care what path I take,

And where it leads it's little I care;

But out of this house, lest my heart break,

I must go, and off somewhere.

It's little I know what's in my heart,

What's in my mind it's little I know,

But there's that in me must up and start,

And it's little I care where my feet go.

I wish I could walk for a day and a night,

And find me at dawn in a desolate place

With never the rut of a road in sight,

Nor the roof of a house, nor the eyes of a face.

I wish I could walk till my blood should spout,

And drop me, never to stir again,

On a shore that is wide, for the tide is out,

And the weedy rocks are bare to the rain.

But dump or dock, where the path I take

Brings up, it's little enough I care;

And it's little I'd mind the fuss they'll make,

Huddled dead in a ditch somewhere.

"Is something the matter, dear," she said,

"That you sit at your work so silently?"

"No, mother, no, 'twas a knot in my thread.

There goes the kettle, I'll make the tea."

~ Edna St. Vincent Millay, born on this day in 1892

And where it leads it's little I care;

But out of this house, lest my heart break,

I must go, and off somewhere.

It's little I know what's in my heart,

What's in my mind it's little I know,

But there's that in me must up and start,

And it's little I care where my feet go.

I wish I could walk for a day and a night,

And find me at dawn in a desolate place

With never the rut of a road in sight,

Nor the roof of a house, nor the eyes of a face.

I wish I could walk till my blood should spout,

And drop me, never to stir again,

On a shore that is wide, for the tide is out,

And the weedy rocks are bare to the rain.

But dump or dock, where the path I take

Brings up, it's little enough I care;

And it's little I'd mind the fuss they'll make,

Huddled dead in a ditch somewhere.

"Is something the matter, dear," she said,

"That you sit at your work so silently?"

"No, mother, no, 'twas a knot in my thread.

There goes the kettle, I'll make the tea."

~ Edna St. Vincent Millay, born on this day in 1892

21 February 2006

Obstacles

The shutters are pushed open by Emilia, and the day admitted. With the first crushing of the gravel under wheels comes the barking of the police dog, Banquo, and the carillion of the church bells. When I look at the large green iron gate from my window it takes on the air of a prison gate. An unjust feeling, since I know I can leave the place whenever I want to, and since I know that human beings place upon an object, or a person, this responsibility of being the obstacle when the obstacle lies always within one's self. In spite of this knowledge I often stand at the window staring at the large closed iron gate, as if hoping to obtain from this contemplation a reflection of my inner obstacles to a full, open life.~ Anaïs Nin, born on this day in 1903

The More Loving One

Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.

Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total dark sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.

~ W.H. Auden, born on this day in 1907

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.

Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total dark sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.

~ W.H. Auden, born on this day in 1907

20 February 2006

Gorey knows best

You will be smothered under a rug. You're a little anti-social, and may want to start gaining new social skills by making prank phone calls.

What horrible Edward Gorey Death will you die?

brought to you by Quizilla

(Via Eclectic Closet)

The mother lode

As Jeff notes, famed editor Robert Giroux just donated over 3,000 pages of "new" Merton material to the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University (where his archives are currently stored):

Makes me wonder what else he's got lying around!!

"I just knew that's Merton's stuff and forgot what it was," said Giroux, a college friend of Merton who later edited many of the monk's books, including his breakthrough work, "The Seven Storey Mountain." [...](The article also includes a photo.)

The donated documents include drafts or proofs of five Merton books.

It also includes an unpublished book manuscript, various essays, letters between Merton and Giroux and a 1940 rejection slip for an early novel.

The donation is the largest addition to the Thomas Merton Center since the monk's death. The collection has 50,000 documents by and about Merton, most of them transferred from Gethsemani in the 1960s. [...]

There is also an unpublished manuscript from the 1960s on art and worship -- Merton's revival of a book that was rejected for publication in the 1950s. Until now, Pearson said, scholars didn't know how hard Merton tried to rehabilitate that book.

"Having parents as artists, being a good artist himself, there was something there he wouldn't let go of," Pearson said. [...]

Giroux's donation, appraised at $911,225, is actually his second major gift to the center. He thought he had provided all his Merton papers in 2001 with a donation appraised at around $210,000.

Samway called Giroux "the best editor America's ever had."

Giroux's authors included poets T.S. Eliot and Pablo Neruda and fiction writers Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Jack Kerouac.

Makes me wonder what else he's got lying around!!

Of lonely hunters

Carson McCullers, born 19 February 1917

Carson McCullers, born 19 February 1917To me the most impressive aspect of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter is the astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern fiction, to handle Negro characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race. This cannot be accounted for stylistically or politcally; it seems to stem from an attitude toward life which enables Miss McCullers to rise above the pressures of her environment and embrace white and black humanity in one sweep of apprehension and tenderness.~ Richard Wright, 1940

In the conventional sense, this is not so much a novel as a projected mood, a state of mind poetically objectified in words, an attitude externalized in naturalistic detail. Whether you will want to read the book depends upon the extent to which you value the experience of discovering the stale and familiar terms of everyday life bathed in a rich and strange meaning, devoid of pettiness and sentimentality.

This book is literature. Because it is literature, when one puts it down it is not with a feeling of emptiness and despair (which an outline of the plot might suggest), but with a feeling of having been nourished by the truth. For one knows at the end, that it is these cheated people, these with burning intense needs and purposes, who must inherit the earth. They are the reason for the existence of a democracy which is still to be created. This is the way it is, one says to oneself - but not forever.~ May Sarton, 1940

19 February 2006

Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock

The houses are haunted

By white night-gowns.

None are green,

Or purple with green rings,

Or green with yellow rings,

Or yellow with blue rings.

None of them are strange,

With socks of lace

And beaded ceintures.

People are not going

To dream of baboons and periwinkles.

Only, here and there, an old sailor,

Drunk and asleep in his boots,

Catches tigers

In red weather.

~ Wallace Stevens

As Anthony Whitting writes, "The middle-class American goes to bed at ten o’clock and haunts his own house by wearing a white nightgown."

Somehow, I began reading this as a 10:00 a.m. poem--disappointment with the morning and the inevitable procrastination of dealing with the coming day. It is now past 11 and I'm still in my pajamas--precipitating a classic case of personal subjectivity affecting poetic meaning.

But it's fun to hang on to misreadings as long as the accurate one is kept close at hand. There is a poet's intention, a reader's response, and the no man's land where both meet to create another experience where nothing can really be wrong--a literary limbo where more is possible.

By white night-gowns.

None are green,

Or purple with green rings,

Or green with yellow rings,

Or yellow with blue rings.

None of them are strange,

With socks of lace

And beaded ceintures.

People are not going

To dream of baboons and periwinkles.

Only, here and there, an old sailor,

Drunk and asleep in his boots,

Catches tigers

In red weather.

~ Wallace Stevens

As Anthony Whitting writes, "The middle-class American goes to bed at ten o’clock and haunts his own house by wearing a white nightgown."

Somehow, I began reading this as a 10:00 a.m. poem--disappointment with the morning and the inevitable procrastination of dealing with the coming day. It is now past 11 and I'm still in my pajamas--precipitating a classic case of personal subjectivity affecting poetic meaning.

But it's fun to hang on to misreadings as long as the accurate one is kept close at hand. There is a poet's intention, a reader's response, and the no man's land where both meet to create another experience where nothing can really be wrong--a literary limbo where more is possible.

16 February 2006

Two forces

From "The Dynamo and the Virgin" in The Education of Henry Adams:

From "The Dynamo and the Virgin" in The Education of Henry Adams:The historian was thus reduced to his last resources. Clearly if he was bound to reduce all these forces to a common value, this common value could have no measure but that of their attraction on his own mind. He must treat them as they had been felt; as convertible, reversible, interchangeable attractions on thought. He made up his mind to venture it; he would risk translating rays into faith. Such a reversible process would vastly amuse a chemist, but the chemist could not deny that he, or some of his fellow physicists, could feel the force of both. When Adams was a boy in Boston, the best chemist in the place had probably never heard of Venus except by way of scandal, or of the Virgin except as idolatry; neither had he heard of dynamos or automobiles or radium; yet his mind was ready to feel the force of all, though the rays were unborn and the women were dead.~ Henry Adams, born on this day in 1838

Here opened another totally new education, which promised to be by far the most hazardous of all. The knife-edge along which he must crawl, like Sir Lancelot in the twelfth century, divided two kingdoms of force which had nothing in common but attraction. They were as different as a magnet is from gravitation, supposing one knew what a magnet was, or gravitation, or love. The force of the Virgin was still felt at Lourdes, and seemed to be as potent as X-rays; but in America neither Venus nor Virgin ever had value as force;—at most as sentiment. No American had ever been truly afraid of either.

Undeconstructible

From John D. Caputo's marvelous essay on Jacques Derrida:

But what his critics missed (and here not reading him makes a difference!), and what never made it into the headlines, is that the destabilizing agency in his work is not a reckless relativism or an acidic skepticism but rather an affirmation, a love of what in later years he would call the "undeconstructible." The undeconstructible is the subject matter of pure and unconditional affirmation--"viens, oui, oui" (come, yes, yes)--something unimaginable and inconceivable by the current standards of imagining and conceiving. The undeconstructible is the stuff of a desire beyond desire, of a desire to affirm that goes beyond a desire to possess, the desire of something for which we can live without reserve. His critics had never heard of this because it was not reported in Time, but they did not hesitate to denounce what they had not read, like the famous signatories of the letter to Cambridge University, who disgracefully declared Derrida's unworthy of an honorary degree because he undermined the standards of responsible scholarship--the most elemental tenet of which would surely have been first to read what you criticize in public (a close second being, if you do read it, try to understand it).(Via The Reading Experience)

It was not surprising that in the last fifteen years Derrida would start talking about religion, telling us about his "religion (without religion)," about his "prayers and tears," and about the Messiah. He would even write a kind of Jewish Confessions called "Circumfession," a haunting and enigmatic journal he kept while his beloved mother lay dying in Nice, a diary cum dialogue with St. Augustine, his equally weepy "compatriot." Modern day Algeria is the ancient homeland (Numidia) of Augustine and Derrida even lived on a street called the Rue Saint Augustin. In this text, the son of these tears (Augustine/Jacques) cir-cum-fessed (to God/ "you") about his mother (Monica/Georgette), who lay dying on the northern shores of the Mediterranean (Ostia/Nice), to which both families had emigrated. This side of Derrida even makes some admirers nervous, for they would prefer their Derrida straight up, not on what seems to them religious rocks.

His critics failed to see that deconstructing this, that and everything in the name of the undeconstructible is a lot like what religious people, especially Jews, would call the "critique of idols." Deconstruction, it turns out, is not nihilism; it just has high standards! Deconstruction is satisfied with nothing because it is waiting for the Messiah, which Derrida translated into the philosophical figure of the "to come" (à venir), the very figure of the future (l’avenir), of hope and expectation. Deconstruction's meditation on the contingency of our beliefs and practices--on democracy, for example--is made in the name of a promise that is astir in them, for example, of a democracy "to come" for which every existing democracy is a but a faint predecessor state.

But if this religious turn made his secularizing admirers nervous, it made religious people still more nervous. For after all, by the standards of the local rabbi or pastor, Derrida "rightly passes for an atheist," which gives secular deconstructors much comfort (but giving comfort is not what deconstruction was sent into the world to do). When asked why he does not say "I am" an atheist (je suis, c'est moi), he said it was because he did not know if he were, that there are many voices within him that give one another no rest, and he lacks the absolute authority of an authorial "I" to still this inner conflict. So the best he can do is to rightly pass for this or that and he is very sorry that he cannot do better. That, it seems to me, is an exquisite formula not only for what might be called Derrida's atheism, but also for faith. Rightly passing for this or that, a Christian, say, really is the best we can do. It reminds me of the formula put forward by Kierkegaard's "Johannes Climacus" (more Socratic figures!) who deferred saying that he "is" a Christian but is doing the best he can to "become" one.

Derrida visits upon all of us, Christian and Jew, religious and secular, left and right, the unsettling news of the radical instability of the categories to which we have such ready recourse and he raises the idea of still deeper idea of ourselves which (religiously?) confesses its lack of categories. He exposes us to the "secret" that there is no "Secret," no Big Capitalized Secret to which we have been wired up—by scientific reason, by poetic or religious revelation, or by political persuasion. We make use of such materials as have been available to us, forged in the fires of time and circumstance. We do not in some deep way know who we are or what the world is. That is not nihilism but a quasi-religious confession, the beginning of wisdom, the onset of faith and compassion. Derrida exposes the doubt that does not merely insinuate itself into faith but that in fact constitutes faith, for faith is faith precisely in the face of doubt and uncertainty, the passion of non-knowing. Violence on the other hand arises from having a low tolerance for uncertainty so that Derrida shows us why religious violence is bad faith. On Derrida's terms, we do not know the name of what we desire with a desire beyond desire. That means leading a just life comes down to coping with such non-knowing, negotiating among the several competing names that fluctuate undecidably before us, each pretending to name what we are praying for. For we pray and weep for something that is coming, something I know not what, something nameless that in always slipping away also draws us in its train.

15 February 2006

Following the pencil trail

From the introduction to Melville's Marginalia Online:

The acclaimed writer of Moby-Dick, Billy Budd, Sailor and other revered works of American literature was also, as might be expected, a great reader of books. Yet few even among American literary scholars are familiar with the scope and variety of Herman Melville's personal library, and the profound influence of his reading on the growth of his intellect and on the composition of his own fiction and poetry. From youth onward Melville educated himself through rigorous, systematic reading, a habit of life and mind he assumed after the bankruptcy and death of his father required him to withdraw from formal schooling. By the time of his death in 1891, Melville’s library numbered some 1,000 volumes before being dispersed among friends, family members, and second-hand book sellers in Manhattan and Brooklyn.(Via pages turned)

Books bearing Melville's autograph and marginalia continue to resurface, bringing periodic gains to our knowledge of his intellectual and aesthetic development.* Since Melville marked and annotated his books with uncommon regularity and precision, the expanding record of evidence reveals his direct engagement with many past and contemporaneous works and figures: the King James Bible, Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, John Milton, Alexander Pope, Arthur Schopenhauer, William Wordsworth, Honoré de Balzac, Matthew Arnold, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and a host of others. An ongoing project with cooperation and support from numerous individuals and institutions, Melville’s Marginalia Online aims to make this wealth of evidence fully and widely available to scholars and students.

Matters of faith

Spending some time getting to know Killing the Buddha...

Revising Night: Elie Wiesel and the Hazards of Holocaust Theology:

Revising Night: Elie Wiesel and the Hazards of Holocaust Theology:

In fact, God's role in Un di velt [hot geshvign] is not entirely unlike that in Night. In both God is wholly and substantially absent. In the Yiddish, though, this is a different sort of absence. It is the immediate, obvious absence faced by the victim rather than the reflective, philosophical absence later experienced by the survivor. It is the difference between an absence felt by a man under duress and one who is trying to rebuild his life.The Temptation of Belief:

Why, they asked me, would a Buddhist spend all this time researching and writing about Christianity? And why that type of Christianity, specifically? It's a good question, one that I am trying to answer as I do the work, which I have become nearly obsessed with. I keep putting off things like turning our guest room into a nursery to read C.S. Lewis or transcribe an interview with a fundamentalist. People are beginning to wonder. I wonder. But there's one thing I know: Jealousy is a powerful force, and I am terribly jealous of the born again.(Via wood s lot)

14 February 2006

Readers wanted

Sam Lipsyte in conversation at the Loggernaut Reading Series:

LRS: What's strange to me is that fewer and fewer people read, and yet more and more want to write. Look at the proliferation of MFA programs, for example. Maybe it's a part of our self-obsessive culture. It's like the credo of The Subject Steve: "I am me." There's more concern with self-expression than there is in trying to connect with another person, than trying to hear someone else's words.

Lipsyte: I think that's absolutely true. There's a lot of interest in just "spiritual creativity "and "unlocking your inner narrative voice" and so on. People are interested in writing a journal and then turning that journal into a memoir. A Romanian philosopher wrote about how the Roman army really entered its decadent phase when everybody wanted to be in the cavalry. They had to outsource to get foot soldiers because all of the sons of Rome had their dads buy them nice horses so they could be these fine-looking cavalry officers. Everyone wants to be a writer, nobody wants to be a reader.

Musée des Beaux Arts

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully

along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

~ W.H. Auden

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully

along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

~ W.H. Auden

13 February 2006

Nothing personal

Julian Barnes on "Lost fragments from the life of Flaubert":

Flaubert is exemplary, indeed talismanic, for the stern separation he made between his public and private writings. His novels are objective constructions which unfold in authorial absence; his letters are a place of riotous opinion-giving and frank emotional unbuttoning. Yet the distance between the two was not empty but connective. It was part of Flaubert’s literary strategy to treat his correspondence as a déversoir, an overflow, an outlet which purged the intrusive self and helped liberate the fiction into its desired impersonality. Three years before Madame Bovary appeared, he bade farewell, in a letter to Louise Colet, to “the personal, the intimate, to everything connected with me”. His “old project” of one day writing his memoirs was now officially abandoned: “Nothing personal tempts me any more”.(Via A&L Daily)

Vanity Falls

The Little Professor finds parallels between Empire Falls and Vanity Fair:

Like that most astringent of Victorian baggy monsters, the rather more concise Empire Falls dwells deep in the realm of utter disappointment: characters repeatedly discover that the most intensely desired objects of their affection, whether financial or physical, prove sadly unworthy. [...]

Despite the grimness, the novel is, in fact, very funny--rather funnier, I think, than Straight Man. Thackeray would have approved of Russo's sense of irony, whether it's applied to the Whiting family woes ("Honus wanted his son to be prepared for the inevitable day when he, too, would lose his marbles and assault Charles' mother with whatever weapon came to hand" [5]) or Janine's husband-to-be, Walt ("He always drank her in with what seemed to be fresh eyes, and she didn't really care if the reason for this might be short-term memory deficiency" [69]). Not to mention a Cat from Hell--perhaps a direct descendant, as I suggested a couple of weeks ago, from Bleak House's vicious Lady Jane.

Camellia

Camellia, it's that moist and sensitive. It runs, instead, so pure through my veins, presses up at wrist and throat so delicate. World, tentative--pressing.

With licked fingers, I cleaned the cut on my ankle, pressed bougainvillea between a hollow sound of the canal at dusk and brilliant ideas. Love, meant to be remembered, rustles as pale liquid in parts of me that live outside at night with the killdeer that must be sleeping in secret in the cold.

Chilled, bare arms in the tunnel light. Breath whistles in the little cup. Stillness of these sheer petals--as cold and white as the moon, as the smeared streetlights of a tired drive.

Tonight is a face in the dark glass. The center, shop, restaurant are quiet. Something was not done. Goodbye. I feel the ghost of an underpass, black park, garage doors. Days don't begin each with the same potential. To believe they did was your protection, as was the morality which made a move a conscious choice. Good for that, but sad somehow.

The misery I hold is good sometimes too, for nights, coming into a cold room, sitting down with my coat on.

~ Killarney Clary, Who Whispered Near Me

With licked fingers, I cleaned the cut on my ankle, pressed bougainvillea between a hollow sound of the canal at dusk and brilliant ideas. Love, meant to be remembered, rustles as pale liquid in parts of me that live outside at night with the killdeer that must be sleeping in secret in the cold.

Chilled, bare arms in the tunnel light. Breath whistles in the little cup. Stillness of these sheer petals--as cold and white as the moon, as the smeared streetlights of a tired drive.

Tonight is a face in the dark glass. The center, shop, restaurant are quiet. Something was not done. Goodbye. I feel the ghost of an underpass, black park, garage doors. Days don't begin each with the same potential. To believe they did was your protection, as was the morality which made a move a conscious choice. Good for that, but sad somehow.

The misery I hold is good sometimes too, for nights, coming into a cold room, sitting down with my coat on.

~ Killarney Clary, Who Whispered Near Me

12 February 2006

Hopkins by the sea

We hiked up two mountains from Taganga to Bahia Concha yesterday, exhilarated by the blues of the variegated sea and our feet and hands climbing dirt, stones, and trees.

I read Helen Vendler's section on "Gerard Manley Hopkins and Sprung Rhythm" while my feet stood on the shore and the waves lapped at my knees. The ebb and flow nearly broke my heart as I read of his "remaking of the body of style" from the beginnings of his work to the end:

Today I am writing this and listening to Joanna Newsom. She sings of "This Side of the Blue"

I read Helen Vendler's section on "Gerard Manley Hopkins and Sprung Rhythm" while my feet stood on the shore and the waves lapped at my knees. The ebb and flow nearly broke my heart as I read of his "remaking of the body of style" from the beginnings of his work to the end:

Hopkins' condensation of the sonnet form to ten and a half lines in "Pied Beauty" matches not only his syntactic condensation and his condensation of metrical movement into spondees but also his condensation of the world's disturbing variety into intelligible anithetical form ("swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim"). For the moment, Hopkins is telling us--through the stylistic body in which his rendition of the world moves--that though the world appears to him infinitely various, it is ultimately intelligible, not through the logically intelligible world of philosophy, nor through the recursively intelligible world of physics, but rather through the unpredictably intelligible world of antithetical sensation, alternately rapturous and painful. As the shocks of original sensation crowd thick and fast on one another, they are rapidly compressed by Hopkins' ecstatically instressing mind into a condensation of their original arrival. [...]There is sand and salt-water staining these pages now.

But in the tragic aggregation of experience, a poetics of pruning and paring will not suffice alone, any more than will a poetics of relaxed sensuous repose. Toward the end of his life, Hopkins writes a group of gigantic sonnets, of which the visibly longest, "That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection" (197-198) spreads across the page in explosive hexameter lines (running to fifteen or more syllables apiece) and hurls itself down the page in twenty-four such lines [...]

When the mind becomes one gigantic cacophony of groans, in eight-beat sprung-rhythm lines prolonging themselves into one undifferentiated monosyllabic vocal disharmony, we have come to the last agony of the stylistic body of poetry.

Today I am writing this and listening to Joanna Newsom. She sings of "This Side of the Blue"

Svetlana sucks lemons across from meReading, listening. Experiences overlap and coalesce into concentric circles of widening meaning.

and I am progressing abominably

and I do not know my own way to the sea

but the saltiest sea knows its own way to me

and the city that turns, turns protracted and slow

and I find myself toeing the embarcadero

and I find myself knowing the things that I knew

which is all that you can know on this side of the blue

and Jaime has eyes black and shiny as boots

and they march at you two-by-two(-re-loo-re-loo)

when she looks at you, you know that she's nowhere near through

it's the kindest heart beating this side of the blue

and the signifieds butt heads with the signifiers

and we all fall down slack-jawed to marvel at words

when across the sky sheet the impossible birds

in a steady illiterate movement homewards

and Gabriel stands beneath forest and moon

see them rattle and boo, and see them shake, and see them loom

see him fashion a cap from a page of Camus

and see him navigate deftly this side of the blue

and the rest of our lives will the moments accrue

when the shape of their goneness will flare up anew

then we do what we have to do(-re-loo-re-loo)

which is all that you can do on this side of the blue

oh it's all that you can do on this side of the blue

10 February 2006

A few by Brecht

Radio Poem

You little box, held to me escaping

So that your valves should not break

Carried from house to house to ship from sail to train,

So that my enemies might go on talking to me,

Near my bed, to my pain

The last thing at night, the first thing in the morning,

Of their victories and of my cares,

Promise me not to go silent all of a sudden.

Contemplating Hell

Contemplating Hell, as I once heard it,

My brother Shelley found it to be a place

Much like the city of London. I,

Who do not live in London, but in Los Angeles,

Find, contemplating Hell, that is

Must be even more like Los Angeles.

Also in Hell,

I do not doubt it, there exist these opulent gardens

With flowers as large as trees, wilting, of course,

Very quickly, if they are not watered with very expensive water. And fruit markets

With great leaps of fruit, which nonetheless

Possess neither scent nor taste. And endless trains of autos,

Lighter than their own shadows, swifter than

Foolish thoughts, shimmering vehicles, in which

Rosy people, coming from nowhere, go nowhere.

And houses, designed for happiness, standing empty,

Even when inhabited.

Even the houses in Hell are not all ugly.

But concern about being thrown into the street

Consumes the inhabitants of the villas no less

Than the inhabitants of the barracks.

Parting

We embrace.

Rich cloth under my fingers

While yours touch poor fabric.

A quick embrace

You were invited for dinner

While the minions of law are after me.

We talk about the weather and our

Lasting friendship. Anything else

Would be too bitter.

~ Bertolt Brecht, born on this day in 1898

(Via wood s lot)

You little box, held to me escaping

So that your valves should not break

Carried from house to house to ship from sail to train,

So that my enemies might go on talking to me,

Near my bed, to my pain

The last thing at night, the first thing in the morning,

Of their victories and of my cares,

Promise me not to go silent all of a sudden.

Contemplating Hell

Contemplating Hell, as I once heard it,

My brother Shelley found it to be a place

Much like the city of London. I,

Who do not live in London, but in Los Angeles,

Find, contemplating Hell, that is

Must be even more like Los Angeles.

Also in Hell,

I do not doubt it, there exist these opulent gardens

With flowers as large as trees, wilting, of course,

Very quickly, if they are not watered with very expensive water. And fruit markets

With great leaps of fruit, which nonetheless

Possess neither scent nor taste. And endless trains of autos,

Lighter than their own shadows, swifter than

Foolish thoughts, shimmering vehicles, in which

Rosy people, coming from nowhere, go nowhere.

And houses, designed for happiness, standing empty,

Even when inhabited.

Even the houses in Hell are not all ugly.

But concern about being thrown into the street

Consumes the inhabitants of the villas no less

Than the inhabitants of the barracks.

Parting

We embrace.

Rich cloth under my fingers

While yours touch poor fabric.

A quick embrace

You were invited for dinner

While the minions of law are after me.

We talk about the weather and our

Lasting friendship. Anything else

Would be too bitter.

~ Bertolt Brecht, born on this day in 1898

(Via wood s lot)

09 February 2006

A great power

Coffee is a great power in my life; I have observed its effects on an epic scale.So writes Balzac in a great piece on my favorite addi--er, beverage. Coffee Literature, a site of Chin Music Press, is definitely worth your time (with many thanks to Bud for the tip!).

This has always been my favorite coffee lit passage:

"Bring on the lions!" I cried.~ Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

But there were no lions. I spent every day in the company of one dog and one cat whose every gesture emphasized that this was a day throughout whose duration intelligent creatures intended to sleep. I would have to crank myself up.

To crank myself up I stood on a jack and ran myself up. I tightened myself like a bolt. I inserted myself in a vise-clamp and wound the handle till the pressure built. I drank coffee in titrated doses. It was a tricky business, requiring the finely tuned judgment of a skilled anesthesiologist. There was a tiny range within which coffee was effective, short of which it was useless, and beyond which, fatal.

I pointed myself. I walked to the water. I played the hateful recorder, washed dishes, drank coffee, stood on a beach log, watched bird. That was the first part; it could take all morning, or all month. Only the coffee counted, and I knew it. It was boiled Colombian coffee: raw grounds brought just to boiling in cold water and stirred. Now I smoked a cigarette or two and read what I wrote yesterday. What I wrote yesterday needed to be slowed down. I inserted words in one sentence and hazarded a new sentence. At once I noticed that I was writing--which, as the novelist Frederick Buechner noted, called for a break, if not a full-scale celebration.

On break, I usually read Conrad Aiken's poetry aloud. It was pure sound unencumbered by sense. If I ever caught a poem's sense by accident, I could never use that poem again. I often read the Senlin poems, and "Sea Holly." Some days I read part of any poetry anthology's index of first lines. The parallels sounded strong and suggestive. They could set me off, perhaps.

This morning, as on so many mornings, I lacked sufficient fuel for liftoff. I looked at the legal pad pages again. A new section must be begun in the book, and a place found to put it. I wrote four or five sentences on a gamble, smoked more to stimulate the brain or stop the heart, whichever came first, and reheated a fourth mug of coffee. After the first boiling, the grounds sink to the coffeepot's bottom. When you reheat it, you call it refried coffee. I already felt like the empty kettle on a hot burner, the thin kettle whose water had boiled away. The top of my stomach felt bruised or burned--was this how mustard gas tasted? I drank the fourth mug without looking at it, any more than you look at the needle in a doctor's hand.

Now, alas, I had cranked too far. I could no longer play the recorder; I would need a bugle. I would break a piano. What could I do around the cabin? There was no wood to split. There was something I needed to fix with a hacksaw, but I rejected the work as too fine. Why not adopt a baby, design a curriculum, go sailing?

Susie Asado

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

Susie Asado.

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

Susie Asado.

Susie Asado which is a told tray sure.

A lean on the shoe this means slips slips hers.

When the ancient light grey is clean it is yellow, it is a silver seller.

This is a please this is a please there are the saids to jelly. These are

the wets these say the sets to leave a crown to Incy.

Incy is short for incubus.

A pot. A pot is a beginning of a rare bit of trees. Trees tremble, the

old vats are in bobbles, bobbles which shade and shove and render

clean, render clean must.

Drink pups.

Drink pups drink pups lease a sash hold, see it shine and a bobolink

has pins. It shows a nail.

What is a nail. A nail is unison.

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

~ Gertrude Stein, born this week in 1874

Susie Asado.

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

Susie Asado.

Susie Asado which is a told tray sure.

A lean on the shoe this means slips slips hers.

When the ancient light grey is clean it is yellow, it is a silver seller.

This is a please this is a please there are the saids to jelly. These are

the wets these say the sets to leave a crown to Incy.

Incy is short for incubus.

A pot. A pot is a beginning of a rare bit of trees. Trees tremble, the

old vats are in bobbles, bobbles which shade and shove and render

clean, render clean must.

Drink pups.

Drink pups drink pups lease a sash hold, see it shine and a bobolink

has pins. It shows a nail.

What is a nail. A nail is unison.

Sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet tea.

~ Gertrude Stein, born this week in 1874

08 February 2006

Constant discovery

I do not accept any absolute formulas for living. No preconceived code can see ahead to everything that can happen in a man's life. As we live, we grow and our beliefs change. They must change. So I think we should live with this constant discovery. We should be open to this adventure in heightened awareness of living. We should stake our whole existence on our willingness to explore and experience.~ Martin Buber, born on this day in 1878

Here's a cool slideshow presentation about his life and work.

Faithfully dangerous

Michael Dirda on Javier Marías' Written Lives:

As I say, this is a delightful volume. Marías closes it with a longish piece about his collection of portrait postcards of writers, meditating on what the various images mean to him: The young Gide, he concludes, looks like "a professional duellist"; T.S. Eliot like "a man who has spent decades combing his hair in exactly the same way." But let me finish with Marías's reflections on a photograph of Rilke:(Via Maud)

"Rilke does not have the face one would suppose him to have, so delicate and unbearable was he in his habits and needs as a great poet. . . . His face is frankly dangerous, with those dark circles under deep-set eyes, and the sparse, drooping moustache which gives him a strangely Mongolian appearance; those cold, oblique eyes make him look almost cruel, and only his hands -- clasped as they should be, unlike Conrad's indecisive hands -- and the quality of his clothes -- an excellent tie and excellent cloth -- give him some semblance of repose or somewhat mitigate that cruelty. The truth is that he could be a visionary doctor in his laboratory, awaiting the results of some monstrous and forbidden experiment."

One glance at Rilke's picture and you'll see that Marías's description is exactly right.

One Art

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

--Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

~ Elizabeth Bishop, born on this day in 1911

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

--Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

~ Elizabeth Bishop, born on this day in 1911

07 February 2006

Lurid lessons?

This year, I've gotten into the habit of posting pictures of each day's birthdays on the bulletin board in class (today we had Charles Dickens, Sir Thomas More, and Laura Ingalls Wilder). I try to say a word or two about who these people were and what they did. However, I've noticed a little trend: Marlowe's birthday was yesterday. Burroughs' on Sunday. Joyce's was the 2nd. Yes, I say what amazing writers they were, but also tend to mention other, uh, interesting facts as well. So yesterday, they heard about this:

Possibly while still at university, he became an agent of Sir Francis Walsingham (c. 1530-90), a statesman and a Puritan sympathizer, in the secret service of Elisabeth I and a favorite of Walsingham's brother, Thomas.Great literature, banned books, pot farms, and unsolved murders: who says these things are mutually exclusive? (Or maybe I've just been reading too much Lemony Snicket...)

Research suggests he was murdered by an agent of Francis Walsingham, for reasons unknown. According to Charles Nicholl (The Reckoning The Murder of Christopher Marlowe, 1994), supporters of the Earl of Essex could have been behind the death. Scholars are still attempting to reconstruct the events. In the common version it is concluded, that after eating and drinking together in a tavern in Deptford, on Wednesday, May 30, 1593, According to the coroner's inquest, Marlowe and his friend Ingram Frizer began to wrangle over payment of the bill. Marlowe wrenched Frizer's dagger from its sheath, and struck him twice about the head with it. In the struggle Frizer got the dagger. "And so it befell, in that affray, that the said Ingram, in the defence of his life, with the dagger aforesaid of the value of twelve pence, gave the said Christopher a mortal wound above his right eye." The dagger went in just above the right eye-ball.

05 February 2006

Respecting intelligence

Joseph Parisi responds to the question, "Do you think there is a place for poetry in the American culture we know now?"

On a related note, I'm reminded of Stephen Mitchelmore's response to John Carey:

The question presumes a kind of necessity. In the marketplace of ideas, I would say no. The question really is: what is its purpose? Well, there isn’t any. It’s like asking what’s the purpose of Mozart? If one is looking for a utilitarian use for such things, you probably won’t find one. In a society like ours, the elective activities available are quite vast. The competition is fierce. Unless the poets themselves become educators, there will never be a larger audience for poetry. Poetry requires a sophisticated level of learning. To get the nuances of poetry requires not only a high level of language learning, but also cultural learning. A few readers of my new book I spoke with recently seemed surprised that they could like poetry. When I was editor of Poetry, I wanted my readers to feel welcome as non-specialists. I wanted to reach as many readers as I could. If you give people something of value, something that respects their intelligence, they will respond.I was happily reading along (more or less) until I got to this last bit. How do you respect someone's intelligence if you're trying to make sure that no one feels alienated? Was this the beginning of Poetry's current preoccupation with mass appeal? As Dan Green asked,

What is a "specialist" reader? Someone who reads poetry? What's a "nonspecialist" reader? Someone who can take it or leave it? Why would poets want to appeal to such a reader?Perhaps a "nonspecialist reader" is someone who hasn't studied poetry at the university level. Yet this line of reasoning still doesn't make any sense. I was 16 when I fell in love with Eliot, Cummings, Yeats, Rilke, Neruda, Plath, Roethke, Dickinson, and others. I didn't love them because I completely understood them. Yet it seems that this trend toward "accessibility" is working against one of poetry's main charms--its incomprehensibility. It takes effort to become on speaking terms with a poem. But God forbid that we make people think. (I've gone off on this subject before.)

On a related note, I'm reminded of Stephen Mitchelmore's response to John Carey:

He thinks that authors write the real thing in order to exclude "the masses" whoever they are (so why didn't Proust and Eliot and Woolf write in Latin?). [...]P.S. A long-lost package that was sent in October finally made it to me in January. Inside was a lovely new copy of James Longenbach's The Resistance to Poetry. Pure happiness.

Luckily I didn't have a guide like Carey to prevent me from reading all sorts of apparently unenjoyable books without shame (e.g. Proust at 15). The books were in English. How much more accessible do you need to be? As a result, my life wasn't dominated by embedded ideas such as the opposition of utility and pleasure. I couldn't tell the difference. My life wasn't too bad, but there was so much more.

Metaphor and Being

Paul Elie on Walker Percy's essay "Metaphor As Mistake" (a personal favorite of mine, found in The Message in the Bottle):

Last April, Ron Hogan posted an insightful exchange between Elie and Pankaj Mishra, author of An End to Suffering. I highly recommend giving it a look (scroll down to the bottom for the first entry and work your way up).

For a metaphor to work it must appeal to another person’s unspoken sense of things--must validate "that which has already been privately apprehended but has gone unformulated for both of us."~ from The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage

This apprehended thing--"fugitive something"--is Being itself. Metaphor is a way to know Being. The structure of the world is metaphorical, and a metaphor bridges the gap between thing and Being--between Self and Other, between perception and reality, between the everyday and the transcendent--by naming it indirectly. "We can only conceive being, sidle up to it by laying something else alongside. We approach the thing not directly but by pairing, by apposing symbol and thing."

The argument is implicitly religious, but only in the last sentence of the essay does Percy invoke the Scholastic idea of the "analogy of being"--the idea that the natural world is the image of the supernatural one, and that we know "not as the angels know and not as dogs know but as men, who must know one thing through the mirror of another."

In the sunroom on Milan Street, he had reached a conclusion akin to those proposed by the others: Merton’s call for a restoration of the metaphors for religious experience, O’Connor’s notion of the artist’s task as the "accurate naming of the things of God," Day’s insistence that the Gospel is an instance of metaphor made real--that the poor stranger is not merely like Christ but is Christ, with all that this implies.

Last April, Ron Hogan posted an insightful exchange between Elie and Pankaj Mishra, author of An End to Suffering. I highly recommend giving it a look (scroll down to the bottom for the first entry and work your way up).

04 February 2006

Against abstraction

Flannery O'Connor on the essence of fiction:

The beginning of human knowledge is through the senses, and the fiction writer begins where human perception begins. He appeals through the senses, and you cannot appeal to the senses with abstractions. It is a good deal easier for most people to state an abstract idea than to describe and thus re-create some object that they actually see. But the world of the fiction writer is full of matter, and this is what the beginning fiction writers are very loath to create. They are concerned primarily with unfleshed ideas and emotions. They are apt to be reformers and want to write because they are possessed not by a story but by the bare bones of some abstract notion. They are conscious of problems, not of people, of questions and issues, not of the texture of existence, of case histories and of everything that has a sociological smack, instead of with all those concrete details of life that make actual the mystery of our position on earth.~ from "The Nature and Aim of Fiction," Mystery and Manners

The Manicheans separated spirit and matter. To them all material things were evil. They sought pure spirit and tried to approach the infinite directly without any mediation of matter. This is also pretty much the modern spirit, and for the sensibility infected with it, fiction is hard if not impossible to write because fiction is so very much an incarnational art. [...] Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t try to write fiction. It’s not a grand enough job for you. [...]

Some people have the notion that you read the story and then climb out of it into the meaning, but for the fiction writer himself the whole story is the meaning, because it is an experience, not an abstraction.

02 February 2006

Couldn't agree more

Kurt Vonnegut on writers' workshops:

You can't teach people to write well. Writing well is something God lets you do or declines to let you do. Most bright people know that, but writers' conferences continue to multiply in the good old American summertime. Sixty-eight of them are listed in last April's issue of The Writer. Next year there will be more. They are harmless. They are shmoos. [...](Via Maud)

Nothing is known about helping real writers to write better. I have discovered almost nothing about it during the past two years. I now make to my successor at Iowa a gift of the one rule that seemed to work for me: Leave real writers alone.

I haven't mentioned the poets in the Writers' Workshop because I don't know much about them. The poets talk all the time, like musicians, and this drives prose writers nuts. The poets are always between jobs, so to speak, and the prose writers are hung up on projects requiring months or years to complete.

The idea of a conference for prose writes is an absurdity. They don't confer, can't confer. It's all they can do to drag themselves past one another like great, wounded bears.

One thing I'm glad about: I got to see academic critics at Iowa. I had never seen academic critics before. They are felt to be tremendously creative people, and are paid like movie stars. I found that instructive.

When I saw my first academic critic, I said to a student, "Great God! Who was that?"

The student told me. Since I was so shaken, he asked me who I had thought the man was.

"The reincarnation of Beethoven," I said.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)